Robin began her career as an engineer, but her true passion has always been storytelling. In 2012 she started her own company with her husband, Cory Childs. Moko Press, LLC was founded as a way to pursue their creative dreams. Now Robin works as an artist, author, educator, and creative consultant.

Main Projects

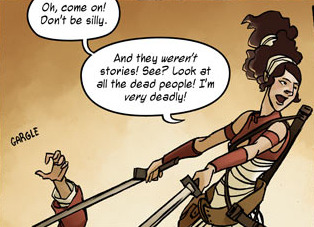

When an irresponsible prince, his day-dreamer sister, and their adopted brother are given a mission by a voiceless goddess of dreams, they will be forced to choose between their future and their family.

Offering manuscript review, story development, and crowdfunding campaign planning to help creative people overcome challenges and realize their dream projects.

Other Hobbies and Obsessions

Reading is probably my favorite activity, when I'm not drawing. And I'm a little obsessed about tea. These days I'm trying to avoid most obsessions though. I tend to become a fan of things very intensely, and there's a big danger in that when people are involved. It's too easy to dehumanize someone when you're getting overly wrapped up and identified with what they do and how they do it. So I am working to admire and

support people who are doing great work, without letting myself reach an obsession point.

So, tell me about your early experience. How did you fall in love with telling stories in pictures?

It's hard to isolate something that's been part of my life for so long, but I'd say what first made me fall in love with the medium was a collection of Calvin and Hobbes that my father brought home after a business trip. I always wanted desperately to be Calvin, as a kid, although I didn't quite have the courage for causing trouble that he did. Adults would always comment to me on how advanced my vocabulary was, and I credit Bill Watterson for a lot of the words I was saying (and almost understanding) at the time.

How long have you been drawing comics?

The earliest works that I have, in comics form, are from when I was around twelve or thirteen. Before that I would draw characters and maps, or write prose, but for some reason didn't jump into combining the two into complete stories until then.

At that age, I did comics about my cats, or about my friends (and our "Evil Sides" that we would transform into) which usually ran about fifteen to thirty pages. They were short and goofy stories, typically humorous in nature.

The comic that I was the most serious about as an early teen was called "Forest Shadows," but I got caught in a common loop that I've seen a lot of young artists struggle with. I'd draw the first thirty pages or so, grow as an artist and writer in the process, and then throw out everything I'd done and start over. I probably started that project at least three times. Re-creating the same character designs and refining the same plot.

I think being caught in that cycle, and realizing how counter-productive it was, informed my personal resolution as an adult to always look forward when it comes to creative work. Otherwise you never push yourself to do new things, and you get stuck telling the same stories over and over.

Can you tell me about your typical day or drawing session? How does your working process flow?

These days my process is constantly in flux as I learn new things, so I'm not sure if I have a "typical" day anymore!

I do have several different phases to making a page. Script, Storyboarding, Reference, Pencils, Inking, and Coloring/Lettering.

Everything starts with the script, but we'll talk more about that process in a bit.

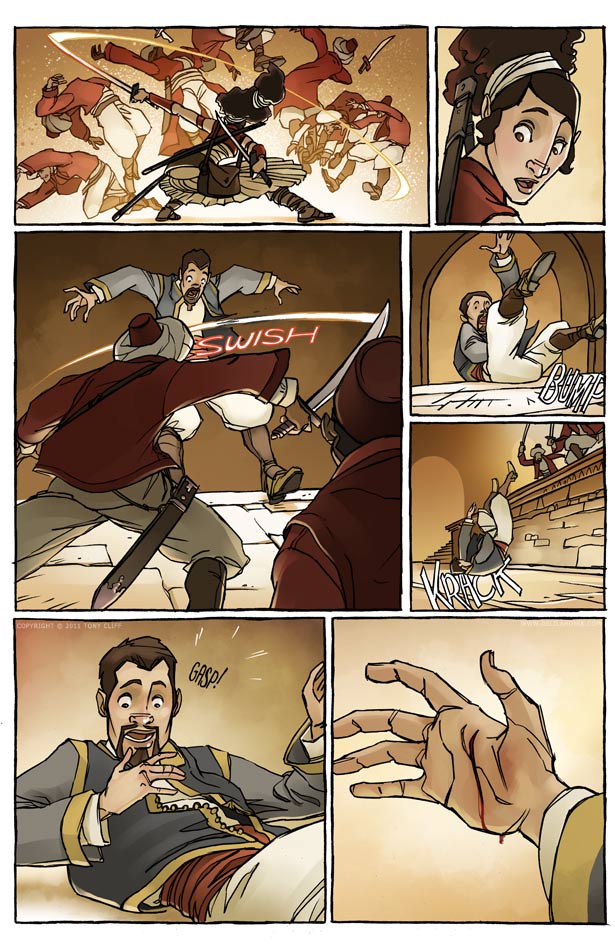

For storyboarding, I consider the order that people speak in, to arrange dialog and establish character location for a scene. I want things to flow logically for the eye. This includes maintaining a consistent direction for motion. I also put a special emphasis on what emotion I want to convey.

Recently I've wanted to include more planning in this process for background elements and value, but I confess that I tend to forget when I'm in the middle of storyboarding. I tend to see it in my mind, but I'd like to stop relying on that. Planning something out on paper usually yields better results than assuming the final image will turn out the way I see it in my head.

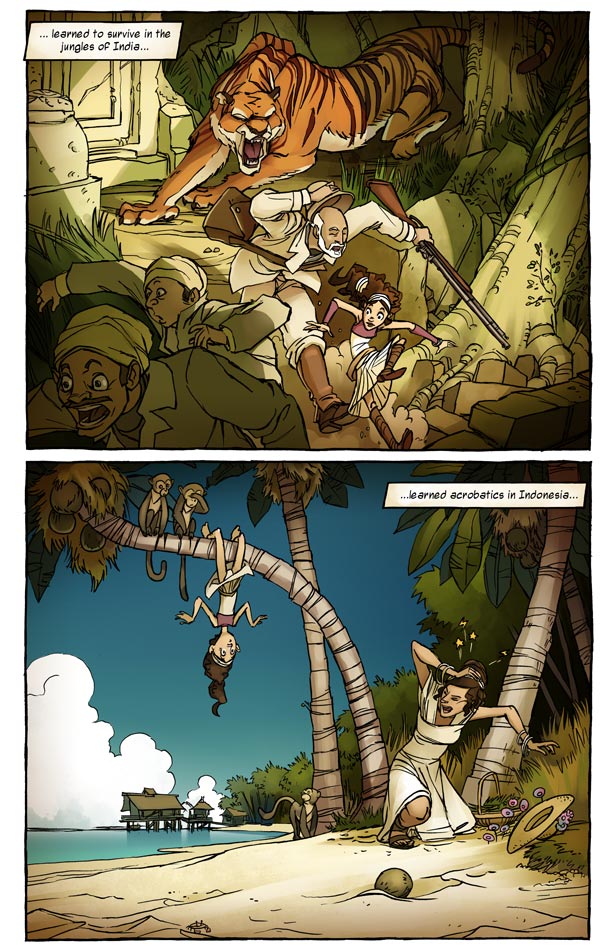

Once I've storyboarded the scene, the reference phase starts. I'll take photographs of myself doing whatever the characters are doing in the panels. This might focus on expressions, camera angles, or movements. Sometimes I'll also use costumes, if there are particularly challenging costume elements. Pakku's glasses, Lu Pai's hat, and Tama's poncho are all examples of costume elements.

Recently for backgrounds, I've also started building 3D models in Google Sketch-up to use as reference. I really enjoy what this adds to the process. Not only does building the set allow me to maintain more consistent perspective, but it forces me to think more about the space itself. What objects make sense for this environment? What do those things say about the person, or people, who live in this space?

I'll also use the model to do my scene planning. Being able to place stand-in figures in an environment and move the camera dynamically around them takes me out of the technical mind-set of a drafts-person, and into the more creative, storyteller's view of a director. How am I guiding the eye? Do the background elements contribute to conveying the feeling and emotion of the scene? Does this angle convey the emotions of the characters? Are we focusing on the people relative to their environment, or creating a more intense emotional moment close in?

Having the dynamic model takes some of the load off of my brain to just process "What would that look like, and how would I draw it?" and instead frees me up to focus on what really matters, visually, for the story.

Once all my planning is done, then I start in on the pencils, using my reference and storyboards to help guide my work.

I'll go through stages of reference-to-imagination ratios. Sometimes, everything is very carefully planned. Other times, I'll skip most of the reference stage. Using a lot of reference can yield images that are very stiff, but not having any at all often creates freer images that look progressively weirder and safer (ie, easier camera angles, expressions, and gestures) with each page. Usually when I get frustrated by one aspect of my work, I'll utilize a different technique for a while, until I get frustrated by something else. I do generally find that my abilities increase faster when I use reference more than less.

One of my current goals is to incorporate animation techniques to find a more in-between drawing style. I'd like my characters to have more fluidity and personality to their lines. If you study an animator's character designs, you'll often feel like they have a lot of life. Even if the character is standing still, there's an implication of movement. I'd love to start seeing more of that energy in my own drawing.

Once pencils are done, I scan in my chaotic scribbles, convert everything into a pale blue line, and print it out on cardstock.

Then I ink that with brushes for the figures and Micron pens for the backgrounds, and scan the result back in. I used to work exclusively with pens. Then, on feedback from readers, switched to just brushes. Then, after more feedback, I settled into a mix of the two. I love the personality and variation of brushes, but they tend to be too shaky for any precise background work. Hard to use a brush and a ruler together. So, when I need more precise background elements, I call in the Microns.

Once scanned, I send my inks off to my color blocker. She sends it back with the character flats. I used to do this part of it, and in truth it's usually not too long a process, but something about it I've always hated. It became prohibitively time-consuming because I'd end up procrastinating what was one of the quickest parts of the process. Working with a color blocker has taken a lot of anxiety off my mind!

After that, it's shadows, lights, bounce lights, textures, and any special effects I want to add.

Wrap it up with lettering and text bubbles, and you have a finished page. Not counting the writing, storyboarding, or reference stages, the illustration of a single page takes somewhere between 8 to 16 hours.

Whew! That was a novel. I will try to answer your other questions more quickly.

Does your production process for a finished piece follow specific steps?

Considering I rarely do anything that isn't a comic page, the steps I just (exhaustively) outlined above are pretty much the process I follow every time.

What media do you work in to produce Leylines?

Cardstock and india ink, combined with Photoshop for colors.

Can you tell me about your storytelling process? Do you prefer to script your stories, fly by the seat of your pants, or somewhere in between?

As I've studied writing, this portion of the process has become more and more involved. I used to only write four comic pages worth of material at a time. These pieces rarely saw much editing. If it felt good enough, I'd dive right in to drawing. I started doing this because of my experience with that early "Forest Shadows" story. On one of my many re-writes, I thought I should write out the entire story in one big script. I got to the end, and no longer felt like illustrating it. I thought that, in the process, the characters had become stiff and uninteresting. I didn't understand the concept and importance of rewriting or editing, which would have solved that problem. Not at age thirteen, at least.

I still think there is a lot of merit to the write-as-you-go method. While it's difficult to foreshadow anything or develop themes that way, sometimes as a creator I need to stay in touch with that raw, creative impulse. At the time, that method was what I needed to create. And creating, doing the work, is what taught me a lot about storytelling. I made a lot of mistakes in that process, but there's some gem segments in there too. I don't think there's really a "wrong" or "right" way to write. The only "right" way, is the way that gets you writing.

Although I now write chapters start-to-finish, I do still storyboard by scene. So I guess that process is still alive today for me. Just adapted a bit.

My current process usually involves finding my theme statement, developing an outline, writing, and re-writing.

I've learned that re-writing is not only inevitable, but it makes for better stories. My inner teen author is horrified by the idea that the first draft is somehow not pure, golden, genius, but it's true. Refinement makes for a more polished result.

How long have you been working on the plot of your current project?

Since about six months before LeyLines launched in 2011. So…Wow, I guess somewhere between four to five years now.

Has anyone told you that you'll never be a successful artist and you'd be better off studying a real field and/or getting a real job?

Haha! Ahhh, considering my education is in engineering and I worked as a Mechanical Engineer for five years, I think we can safely say that, while those exact words weren't used, the message came across. So I've studied a "real field" and I've had a "real job," and I can say with certainty that doing a "real job" that you hate is not worth it. It was damaging to my mental, physical, and psychological well being.

I learned a lot, and I was good at it, but ultimately I have no desire to be a good engineer. I want to be a great storyteller. I won't find that spending most of my time and energy on something that makes me miserable.

What keeps you devoted to telling the story you’re telling?

The first long-term project I did, I was still firmly in denial about how much storytelling mattered to me. It was "just a hobby." A hobby that I worked on for eight years. All through college and into my first few working years. When I finished that story, I thought, "Okay, I finished what I started, so now I can close that silly chapter of my life where I needed a silly hobby and commit to my real life and my real job and my real career."

It felt like I was drowning.

That's when I realized that this wasn't just a hobby, and it had never been a hobby. It was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life, and I'd never been able to admit it to myself because of the values I'd internalized growing up. Once I challenged those notions, I started to invest in my creative career more strongly and consciously. Cory and I started Moko Press, and I started working on LeyLines. A year or two after that, I left my engineering job. I'm still not working on art and storytelling full-time, but I'm doing so many new things in creative fields that I'd never dreamed possible before.

I'm devoted to telling stories in the same way I'm devoted to breathing. It's a part of who I am. I need it to survive.

What message do you hope your readers will come away with?

My current work focuses on claiming one's own identity. I've struggled with embracing myself and my own dreams, coming into conflict between what I am and what my parents wanted me to be. Every character in my story wrestles with this same dilemma in some way. Sometimes with family, sometimes with society, sometimes with themselves.

I also struggle with chronic depression, so while my external battle is with societal and familial expectations, there's also an internal conflict with my own negative core. That also comes out with several of the characters in my story, and it's something I am open about in my blogs.

Depression is so stigmatized in our culture, so it's easy to feel alone, which is in itself a trap, because depression thrives in secrecy and isolation.

I try to share my experiences in the hope that it will let others know they're not alone. I've had a few letters about how sharing my difficulties online has helped other people get through their own darker days. That's an amazing honor and gift, to hear things like that.

The message I'd like people to take away from my work are that we all have to claim our own identity, but that doesn't mean we have to be alone to be ourselves.

Bravo, Robin Childs! I tip my hat to you, and read your future work with relish!